The United Cigar Stores of America

This is a cover story I wrote and researched for Cigar Magazine. A tale of Americana, it maps the ascent and descent of United Cigar Stores, a former gathering spot within communities across the country.

*****************

From the 1890s through the 1960s, United Cigar Stores graced more than three thousand American streetcorners. By the 1970s, they have virtually disappeared.

*****************

It was a cool autumn day in 1960 and Lew Rothman was working in his parents' Harlem, New York, United Cigar shop on 125th Street and Seventh Avenue. Amid the dark wood fixtures, Rothman noticed a striking man clad head to toe in army fatigues — a man who seemed to have a taste for expensive cigars.

Rothman was caught off guard that the officer would not speak directly to him, but instead stood aside while a nearby military aide handled the cigar purchase. The aide insisted that his boss be given nothing less than the shop's best box of cigars. Rothman then racked up his biggest sale since his family began running the shop: $17.50 for a box of La Corona cigars, which amounted to thirty-five cents per cigar — fairly pricey in 1960. It wasn't until later that week that Rothman saw a photo in the Sunday edition of the New York Times and realized his customer's identity: Fidel Castro.

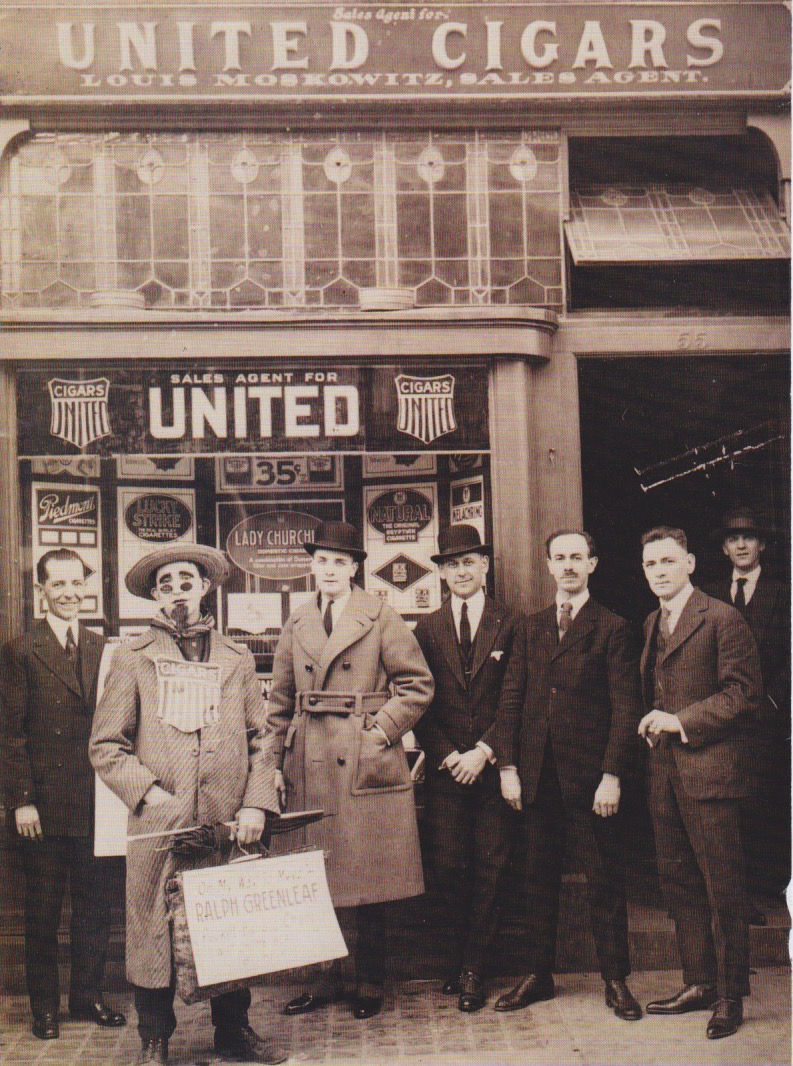

Although Cuban leaders were not typical customers, the United Cigar chain, in its heyday, dominated the American cigar scene and was the social — and sometimes even political and legal — headquarters of any block they occupied. And they were on a lot of blocks: at the apex of United’s popularity, there were three thousand stores on American streetcorners from New York City to Chicago, Los Angeles to Akron, Topeka to Santa Cruz. But these numbers don’t even begin to tell the whole story of United’s significance. From the 1890s through the 1960s, these stores were community magnets — and almost exclusively male. They were what neighborhood taverns were in the 1970s and what, to a lesser extent, gourmet coffee shops were in the early 1990s.

That's the way Joe E. Berry Jr. of Columbia, South Carolina, remembers the United Cigar store. He dropped in to Columbia's United Cigar two or three times a week in the late 1950s, about the time he began his law practice. "My secretary knew to call for me there. You could find a number of lawyers there, or businessmen on their way to the bank. Politicians would come by. They'd have coffee and lots of people smoked," Berry said. "The beauty of the store was that it was a gathering place for businessmen and attorneys in the downtown area — a place to just enjoy each other's company. We'd talk about decisions that had come down at the courthouse, or sports and politics, all from the comfort of one of the booths or tables in the back of the store."

The famed United Cigar chain began as a family business in 1891 in Syracuse, New York, after brothers George and Charles Whelan took over the tobacco brands and factory of John P. Hier and began manufacturing, wholesaling, and retailing both cigars and tobacco. The brothers enjoyed such success in Syracuse that they expanded the retail business to other cities in New York, including Manhattan, in 1901. At that time, they changed the company's name from C.A. Whelan & Company to United Cigar Stores.

Unlike other tobacco shops of the time, which were often somewhat dingy and limited in wares, United stores were brightly decorated and always amply stocked.

"The idea of a clean, modern, well-lit, and well-laid-out store designed for the sale of cigars was novel at the time and contrasted with the dark, cluttered stores that were the norm," said Joe Parker, a contributor to Tobacco in History and Culture: An Encyclopedia, published by Thomson Gale.

The Whelans' first New York City store was in the financial district and displayed an impressive array of cigars stacked from floor to ceiling. Although a bit cramped at only ten feet wide with a seven-foot display window, the shop gave United its start in New York City. "Just a few days after opening the first New York City store, United acquired seven stores from another operator in the city and converted them," Parker said. United later opened as many as 160 shops in New York City alone.

As the cigar chain expanded, it became part of the American Tobacco Company empire, which controlled about 90 percent of the tobacco market in the early 1900s. United Cigar played the role of American Tobacco's retail arm until the monopoly was broken up in 1911. United Cigar stores continued to pop up across the country until bankruptcy disrupted the business right before the 1929 stock market crash. Two Canadian brothers named Morrow then took control of United Cigar, later selling it to Phoenix Securities, a company that specialized in bailouts. Phoenix was ultimately able to help United get back on its feet.

Spanning the US, United stores offered more than just a corner store good for the periodic cigar or a carton of cigarettes. They became community gathering points, often with a men’s club atmosphere. Some had back rooms where guys escaped to games of pinochle or dice, while others provided tables at which customer could sit down, socialize, read, and smoke—all for the price of a five-cent cigar.

United's regular customers would stop by their favorite location several times a week for a smoke and a chat and, as a result, the stores achieved neighborhood landmark status. "The store was a fixture in the neighborhood," recalls Alex Friedlander, the grandson of an owner of one such store in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn. "Anyone who lived in the neighborhood at that time remembers it."

Interestingly, the success and expansion of United Cigar reflected some of the cultural dynamics present at the turn of the twentieth century. "Cigar shops became like bars. Cheap cigars became a rite of passage for American males, just like having a beer in a bar. A cigar store was a place without women or kids," said Dr. Jordan Goodman, editor of the Thomson Gale tobacco encyclopedia. Also, according to the encyclopedia, "tobacco shops were a place of leisure and refuge,” and possessed "special qualities — warmth, camaraderie, and congeniality — that appealed strongly to the male senses. It became a pleasantly informal neighborhood forum with back rooms for pinochle, stud poker, or just plain conversation.”

In Santa Cruz, California, for example, the traditional masculine atmosphere was made up of boisterous fishermen who got together at United during salmon and steelhead season for fish tales and tobacco. "[United] opened up early in the morning during fishing season," said Santa Cruz resident and fisherman Bob Ralston, who spent a lot of time at the shop during the 1940s and '50s. "It was a hangout for fishermen. We'd go to talk about fish. Of course, fishermen are liars," he laughs. "Every time they tell a fish story, the fish gets bigger and bigger.”

"Even the local game warden would come by every evening to talk about hunting and fishing with the guys," said Ernie Kinzli, a former employee of the Santa Cruz store.

"People just came in to sit down and talk and smoke. It had a homey atmosphere. You could just go in and shoot the breeze; no one ever rushed you out of the store," Ralston said.

Not only was the Santa Cruz United perfect for conversation and cigars, the Pacific Avenue shop always made sure to offer the special products a fisherman might need to get through his day, like equipment and bait. "Just about anything you wanted, you could find there," Ralston goes on. "They had coffee and doughnuts too."

At other United locations, however, the camaraderie often took the form of gambling. Alan Falk of the University of Miami Medical School is the grandson of Henry Wise, who, around the time of the Depression, owned and managed several United Cigar stores in Akron, Ohio. Falk describes his grandfather as a larger-than-life character who had played professional football and hung out with the Wright brothers. "He also ran messages by foot from the front lines to headquarters in France for army intelligence during World War I,” Falk said. But the war stories told by Henry Wise were most often about United Cigar, Falk recalls. “What I remember about his cigar store was that he used to have a craps game in the back room. He sometimes would have to throw guys out the back door by the seat of their pants for getting too drunk, or gambling problems.”

While the two Harlem stores owned by the Rothmans during the 1950s and 1960s didn't have any tables or back rooms for craps, gambling was also a part of the neighborhood scene. The Rothmans' regulars would gather every afternoon at 3:30 sharp, awaiting the fifth edition of the paper, which revealed the winning numbers for the day in New York's Mob-controlled numbers racket. According to Lew Rothman, this was quite an event, particularly at the shop on 125th Street and Seventh Avenue — an especially convenient location for those who played the numbers. "The largest bookie was in the basement of Herbert's Diamonds on the northeast corner of the street. Our shop was on the northwest corner," Rothman said. "They'd get paid off real fast."

Mom-and-pop shops like the Rothmans' were commonly known as "agency stores," which were basically United Cigar franchises. United began offering these businesses before the stock market crash and, by the 1930s, many of the United stores were family-owned and -operated franchises. The agency stores were extremely simple to set up and run, as they were geared for people with no previous retail experience, like retired postmen or police officers. "The company told you everything — the cost of a product and what to sell it for," Rothman said, adding that it was an easy way to be in business, and that even the dark wood fixtures came directly from United Cigar. "The wall behind the counter had thick, wood cabinets for tobacco products. It was like a rudimentary humidor. You'd soak these clay-lined blocks to keep the tobacco fresh," says Rothman. But, generally, he says, humidification wasn't needed because there was such a fast turnover in products. "If you ran out of something, you'd order it and have it in a day or two. There wasn't any inventory," he remembers. ''We just knew what we had on hand by what we sold all the time.”

Around the same time that United began offering agency stores, the Whelan family launched Whelan Drugs, prompting United to begin incorporating the drugstore element into its tobacco shops. Both United and Whelan Drugs provided a vast catalogue of available products to their merchants. "Shop owners could buy everything from this one source. It was like a giant cooperative,” Rothman said. "They had everything from toys to stationery, to cigars and aspirin. You could buy anything that was less than one square foot in size — paper clips, envelopes, shoe polish, arch supports, and shoelaces. You name it, we had it," he said of his parents' stores, yesteryear's version of today's 7-11

Following the Depression, other agency stores with this expanded product line began to open up. Harris Miller, Alex Friedlander's grandfather, opened his own United Cigar store, calling it Miller's Cigar Store, in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, on the corner of Utica Avenue and St. John's Place. In addition to the usual cigar inventory, this store boasted a lunch counter and soda fountain — and happened to serve the best egg creams in New York, modestly recalls Ellen Binder, granddaughter of Harris Miller. She and her cousins loved visiting the family store, where they were given paper sacks to fill with all the candy they wanted.

"It was really neat having a candy store. The cigars and cigarettes were incidental to me," Binder remembers fondly. She grew up close to the store and, eventually, her parents took over, though her grandfather still frequently checked in. "He was always dressed in a suit, tie, and hat," she said. "He was like the overseer of the store. He'd sit in a corner where there was a Formica counter and he'd watch over everything with pride. He was an extremely proud man.”

Other United Cigar stores were crammed with an assortment of merchandise, leaving little or no room for even just a few small tables, let alone a lunch counter. No matter what the decor, though, the vast array of cigars and tobacco was always the main attraction. This is certainly how Ellen Binder remembers her own family's shop. "There was a room off to the side from the counter where the humidor was. It was the size of a large closet and was filled from floor to ceiling with cigars," she said. The cigars sold by United also tended to be the better-quality smokes of the day. "The least expensive cigars we had were five cents," Lew Rothman remembered. "There was the Royalist and the John Ruskins — and they were great five-cent cigars. The most expensive cigar was thirty-five cents.

Typically, most United Cigar stores were family-run like the shops of the Millers and Rothmans. And running a neighborhood smokeshop usually required week after week of long hours for just about every member of the family who was old enough to help out. Lew Rothman pitched in after school at his parents' first shop, which they tended seven days a week, every day of the year, from six a.m. until one a.m. "I'd take the A train up there every day after school,” he said. "We were open before and after everyone else."

Of course, such schedules meant that owners sometimes needed a break — the very reason Rothman's parents sold their first United Cigar store in 1964. After a much-deserved two-year hiatus, they opened another shop on 125th Street and Lenox Avenue, where Lew Rothman began working full time.

Similarly, the shop belonging to Harris Miller also became a family effort. Rosie Miller, daughter of Harris Miller and, later, mom to Ellen Binder, started working in the store as a little girl. After her marriage to her childhood sweetheart George Binder, the newlyweds took over daily operations of the shop's six-day-a-week schedule. "My parents were hardworking cigar-store owners six days a week. But it was like a twenty-four-hour thing. My father left for work at five a.m. and stayed there until my mother relieved him at about eleven in the morning. She'd stay until three or four in the afternoon before heading home to make dinner. My brother worked there at night making up the newspapers. Back then, they had to be put together by hand," Ellen Binder said, thinking back to the low-tech world of her childhood. "Sunday was the day off. "

United's storeowners spent so many hours manning their shops that many grew to view their customers as extended family. Even though Lew Rothman lived in Queens, he became acquainted with the regular customers in Harlem and even knew what they wanted before they asked for it. "I'd see a guy coming down the street and I would have his cigars on the counter when he walked in," he says.

Just as the rest of 1960s Harlem attracted various celebrities, so did the Rothman family's cigar shop. Rothman remembers waiting on such customers as Sugar Ray Leonard and Brooklyn Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella. ''The head of the NAACP at the time used to come in. A lot of boxers and musicians too," he said.

The Millers' store in the Crown Heights neighborhood in Brooklyn also had its share of celebrity visitors. Ellen Binder remembers entertainers stopping at her family's shop before boarding the Catskill Mountains-bound Short Line bus, which stopped right outside. "Some comedians — before they were big names — would catch this bus to their performances." Actor Fyvush Finkel, perhaps best known for his longtime participation in Jerome Robbins's Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof, used to buy his bus ticket in the Binders' store, she said. Opera star Robert Merrill also came in; in fact, Ellen Binder's mother once paid his bus fare! Those entertainers were usually on their way to perform in the "Borscht Belt," a predominantly Jewish resort area in the Catskills.

Despite the popularity of the friendly cigar-store atmosphere, these shops were unable to survive. "The decision was made to get out of the cigar-store business, and United began selling off and closing stores," writes Joe Parker, in Tobacco in History and Culture. After a few years, only the distribution end of the business and the drugstores remained. The agency stores exerted a valiant effort to hold, but they eventually disappeared too. Sadly, neighborhood United Cigar stores lived on only in Canada, where the Morrow brothers had introduced the chain way back in the 1920s.

And then, several changes began to occur, ultimately leading to the end of United's distribution business, which was based in New York State. In 1964, the US Surgeon General's report on tobacco-related health dangers was released, prompting many states to increase taxes on tobacco. Citing the report, the state of New York doubled its taxes on cigarettes, which especially hurt New York City, whose tobacco taxes were already higher than the national average. These tax hikes impelled storeowners to buy tobacco from sources other than the United Cigar distributor. “All the storekeepers started driving to New Jersey to evade the tax. Eventually, no one in New York was buying tobacco from United Cigar anymore,” says Lew Rothman. “It spelled the death of United Cigar in New York because that’s where most of the stores were.”

In the mid-1960s, neighborhoods began to evolve and the need for a local cigar shop changed as well. In the case of the Brooklyn store, the Binder family sold it to an employee. But the Crown Heights neighborhood in Brooklyn was beginning to develop from a mainly Jewish area to a Caribbean neighborhood. "The cigar store didn't cater to their interests but it still remained open for a time," said Alex Friedlander.

As for the downtown Columbia, South Carolina, community, the evolutions that occurred pushed the United Cigar store out completely. For years, downtown Columbia had been an epicenter of business. "There were between two hundred and three hundred lawyers concentrated in that part of town,” says Joe Berry, the attorney who frequented this United location in the fifties. "Then everyone became more scattered." So, because the business district expanded in this way, the need for a central hangout disappeared.

In Santa Cruz, Mother Nature had her way with the United store, in the form of a flood that put all of Pacific Avenue under water in 1955. "Water was up to the second story windows," Bob Ralston remembers. The United Cigar store changed locations at that time but, according to Ralston, never returned to its former status. "It was the beginning of the disappeared too. Sadly, downfall, I think. I was shocked when I found out it closed. It was kind of a landmark."

Today, the United Cigar stores so fondly remembered by so many Americans are pages in history, recollections of a much simpler time. "United Cigar is an anachronism — a thing of the past," Lew Rothman said. "Nothing ever replaced United."

Ellen Binder agrees. "There never will be any kind of place like that again," she said. "Two years ago, I went back to see the old neighborhood. There's nothing there now. My family's cigar store became a convenience store. I went in to see if any of the old fixtures were there. But it's all gone except for the memories.”

In so many ways, and to so many people, those United Cigar stores reflected the time in which they prospered. They are reminiscent of an era during which close-knit communities were the norm, and a time when not knowing a neighbor two doors down was simply unheard of.

Times have indeed changed. The bonds that were once the draw of the local cigar shop have dissolved into our country's multitasking, no-time-to-spare manner. The United Cigar chain has vanished into today's fast-paced, high-tech world, making way for the conveniences of drive-through coffee shops and online malls, where one can buy anything from hardware to hair care, and, of course, cigars. But perhaps in our quest for speedy shopping, we have left behind the truly important thing that the United Cigar stores offered to so many American neighborhoods: a sense of community and belonging — something that has possibly never been more in need.

Gallery