Past Presence

This is an article I wrote for South Magazine about Fort Pulaski in Savannah and a group of Civil War reenactors.

On a foggy November morning at Fort Pulaski, a sea of men in blue uniform fill the parade grounds. Two platoons of Union soldiers stand within the brick walls amid the haze, taking orders for drills. A fife and drums can be heard playing in the background while the sergeants shout out orders to their men. The sun is just coming up and everything seems just as it might have been during the Civil War to re-enactor Ken Giddens, who is playing the role of the first sergeant this day.

“It was a very unique moment with the fog and not being able to see anything that wasn't of that period and having the music play while commands were being given,” Giddens recalls. “It was a very surreal moment. You don't get those too often but you always remember them when you do.”

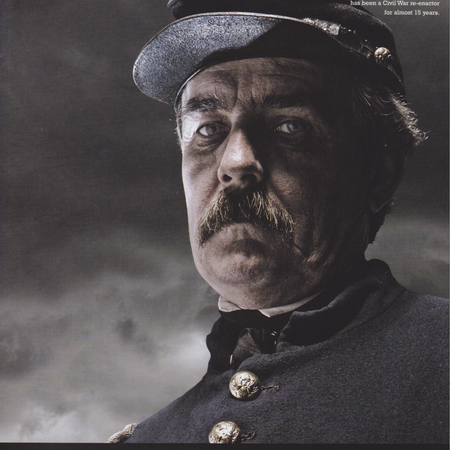

Giddens, 49, has been a Civil War re-enactor for almost 15 years and counts that morning a few years back among his favorite memories. The Jacksonville resident and member of the 48th New York Infantry was back at the fort again this April for the 144th commemoration of the siege by Union forces.

The actual scene during the siege of April 1862 would have been far different than what Giddens experienced a few years ago. He wouldn't have seen early morning drills but rather cannon smoke in the distance. He wouldn't have heard music, but rather a barrage of explosions lasting 30 hours. That's how long it took the Confederates to surrender to Union forces that had taken position one mile away at Tybee Island.

For the first time in the fort's history, this year the commemoration of the siege included a “living history” program at Tybee, in addition to the program at the fort. “We did this to present a balanced story. The occupation by the Confederates is only half the story,” explains Charles Fenwick, superintendent at the fort. “There were 11 Union batteries on Tybee, so we had uniformed portrayal at one of them with cannon fire.”

The living history program adds another element to the commemoration, according to 50-year-old reenactor Eddie Cockman, who was at the fort as a Confederate soldier. “Without us, when you come through the gate of the fort. it's just walls standing there,” he says. “We bring the battle to life.”

With the Union soldiers on Tybee Island firing the cannon from their post and the Confederates firing back from the fort, it was a powerful and exciting scene for visitors. Visitors at the Tybee site could hear cannon fire at the fort and also look toward it and see a Confederate flag flying “from there like a neon sign,” Fenwick says.

Being able to appreciate that distance between Tybee Island and Fort Pulaski on Cockspur Island is key to understanding the battle. “The only way to appreciate what happened is to stand on top of the [fort] walls and look out to Tybee. Then, you see what a long-range battle it was,” says park ranger Mike Ryan.

The distance wasn't the only thing that made this Civil War battle unique. “Most battles are disorganized chaos. Soldiers are all together. This was so different. There was no hand-to-hand combat. They couldn't even really see each other,” Ryan explains.

The siege of Fort Pulaski was also unique in the worldwide impact it had on military thinking. The fort was part of what's known as the Third System of coastal fortifications built during the first part of the 1800s in response to the War of 1812. “It was built to protect peace, prosperity and the American way of life. People appreciate that today just as they did 100 years ago,” Ryan says.

In order to protect those values, the fort was built with seven and a half-foot solid brick walls that were considered to be unbreachable. Ryan likens it to the “stealth bomber of that age.”

With access to the smooth-bore cannon and mortars of the time, the Confederates weren't worried about an attack from Tybee Island. The distance between the fort and the Union weapons was more than twice the effective range of the typical guns. Robert E. Lee had even visited the fort prior to the siege and reassured the Confederates, saying that from Tybee Island Union forces could “make it pretty warm for you here with shells, but they cannot breach your walls at that distance.”

But Robert E. Lee's statement and the thinking of the day proved to be wrong. The Union forces had 10 new rifled cannon with a range of almost five miles. The projectile on these “was like a tight spiraling football, with two to three times the range of smooth-bore. They were also more accurate and aerodynamic,” Ryan says. Those projectiles managed to break through the walls of the fort on the southeast corner. Some of them are still embedded in the façade.

With concerns about a gunpowder magazine on the opposite side of the fort, the Confederates

surrendered after that break occurred. News of the siege traveled around the globe. “For centuries, nations around the world—they had built castles and walled fortresses. Everyone had a stake in this battle. The influence was everywhere,” Ryan says. What the Union forces accomplished “didn't make forts obsolete overnight. The Federals spent a lot of effort to replace the bricks and repair the fort. What happened showed their vulnerability, though,” he says. Such forts could no longer be considered invincible.

That wasn't the only battle fought at Fort Pulaski, Ryan says. “There was also the battle of boredom. When they weren't doing military duties, soldiers here played baseball games and had sack races.” Re-enactors often showcase those kinds of things for the public, to illustrate what life was like during the war. The Fort Pulaski program in April was more like that. “We were mostly talking to the public about what [soldiers] were doing there, the life they would have had and what they would have eaten,” Giddens says about his group's portrayal of the 7th Connecticut on Tybee Island.

Re-enactments can run the gamut from something like the Fort Pulaski program to events known as immersions, Giddens says. “There is no public—no one there to see us. With those, we're trying to recreate a sense of what it would have been like in the 1860s.”

The immersions are typically held over a weekend but can last as long as a week. During that time, nothing “modern” is permitted, Cell phones aren't allowed and neither are wristwatches or cigarettes. “If someone wants to smoke, they have to get cigars or pipes, even though certain cigarette brands were around at that time. We're portraying what a common soldier would've been like,” Giddens says. “And we are kept to only speaking and acting as if it's 1860. We stay focused on not getting out of character.”

The re-enactments create strong camaraderie among the participants— whether they wear a blue or grey uniform. A rivalry between the North and South isn't really there, according to Giddens. “As far as overall attitude, a lot of guys go both ways. They have both uniforms,” he says.

Cockman agrees the two groups get along, but he won't portray a Union soldier, even when there aren't enough of them for a battle. Four of his great great-uncles fought for the Confederacy, he explains. “l have a joke I tell everyone about that. I tell them that I put on a Union suit one time and went to the relatives' graves and there was dirt turned up. It was from them rolling in their graves,” Cockman says.

For Fort Pulaski, bringing in re-enactors —in both blue and grey uniforms—helps tell the story. “We don't want to recreate the terrible event. We want to commemorate it and educate people on what took place,” Ryan says. “It's about bringing these stories alive, bringing the resource to life. The groups show pretty much what it was like during the Civil War. The only way to demonstrate is through taste, touch and smell,” Fenwick says.

For both the re-enactors and the fort, the goal is to bring history to life and keep it alive.

Gallery